This story is part of a special series celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Fast Company Innovation Festival.

Ted Sarandos stepped off an electric golf cart in the Albuquerque summer heat, ducked into a state-of-the-art soundstage, and entered another world.

“Looks just like a hospital,” he said as a production assistant guided him past wheelchairs and a mannequin strapped to a gurney. This was the set of Pulse, a new original series that unfolds in Miami’s busiest Level 1 trauma center, and as word spread that the boss had arrived, co-showrunner Carlton Cuse emerged from what looked like an operating room and shook Sarandos’s hand.

“That’s a cut!” someone yelled, as Cuse, best known as a showrunner on ABC’s Lost, began a tour of Pulse’s faux hospital, featuring a two-story entryway, full-on emergency room, scrub-in area, and long hallways where actors could perform “walk and talk” scenes without running into a wall.

Pulse, set to debut next year, is Netflix’s first medical procedural, or “case of the week” show. Along with crime shows like Law & Order, medical procedurals have long been the bread and butter of traditional TV. Viewers love them because they reliably deliver on an expected formula (and can be watched out of order). And they cost less to make than serialized, prestige dramas.

“What you really hope,” Sarandos said as he traversed the expanded Netflix Studios Albuquerque—12 soundstages on 108 acres, with a solar array and battery storage system, geothermal heating and cooling, and 50 electric vehicle fast chargers—is that Pulse “is a long-running show so all this investment makes more sense.”

Studio lot? OG showrunner? Long-running medical procedural? Was this 2024, or 1994, the year that NBC’s ER made George Clooney a star? It seemed Netflix had spent more than a decade disrupting the linear television business only to . . . replicate the linear television business. Lately, the streaming leader had begun venturing into more areas that once defined old-fashioned TV: live event programming, sports, and even advertising. You could call these events ironic. Over its 27-year history, the company had innovated in truly novel ways: DVDs by mail, streaming at scale, an algorithmic version of the traditional “channel guide,” becoming the world’s first and only truly global entertainment platform. But was this the ultimate innovation: returning, triumphantly, to where TV began? I asked Sarandos whether Netflix had succeeded in part by infiltrating Hollywood, Trojan-horse-like, as a tech-driven curiosity—then slaughtering its rivals from within. He rejected the analogy.

“I’ve never viewed disruption as a way to kill anything,” Sarandos told me. “I’ve viewed it as a way to save it. And I actually think that’s what we’re doing.”

Last year, for the first time, fewer than half of U.S. households subscribed to traditional cable and satellite services. There are seemingly countless streaming companies competing to lure those viewers—Disney+, Hulu, Max, Peacock, Paramount+, Apple TV+, and Amazon Prime Video, among others. Most are struggling to turn a profit. Amazon does not report subscriber numbers (Netflix plans to stop doing so next year), which can make comparisons difficult. But by one metric at least—profitability—Netflix dominates.

Netflix’s annual revenue last year reached nearly $34 billion, with net income of $5.4 billion, a record for the company and a 20% increase over 2022. This is even more notable given that just two years ago, Netflix appeared to have peaked: Its subscriber numbers had fallen, and its competitors were upping their spending. Now Netflix is on top again. During the company’s Q2 earnings call in July, it announced that it had exceeded quarterly financials and added 8 million subscribers (almost double what analysts had forecast). Its subscribers generally pay more than $11 per month, roughly the industry average. Capitalizing on its robust production pipeline, seamless user interface, and global reach, Netflix is making entertainment for everyone everywhere all at once. And especially for the last 10 years, there is one person most associated with its momentum: Ted Sarandos.

When I met him, in June, he’d just returned from his latest international trip. First, he’d visited Noah Baumbach on the Tuscan set of a movie he’s directing for the streamer. After dinner with the cast (Clooney, Adam Sandler, Laura Dern), Sarandos headed to Copenhagen, where he sat down with the Danish culture minister. Next, he flew to Amsterdam, Netflix’s EU headquarters, where he addressed more than 500 employees and visited the sets of two Dutch-language shows. Then he headed to Rome, to meet with the city’s mayor and Italy’s ministers of culture and finance. While there, Sarandos squeezed in a dinner with the prominent Italian writer-director Paolo Sorrentino.

On the way back to L.A., Sarandos stopped in New York (to speak to investors and analysts at Bank of America’s Media in Montauk event) and Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, where he attended a gathering hosted by venture capital firm TCV, an early backer of Netflix. Finally, he strode into Netflix’s Icon Building in the heart of Hollywood and personally retrieved me from its Emmy- and Oscar-strewn lobby.

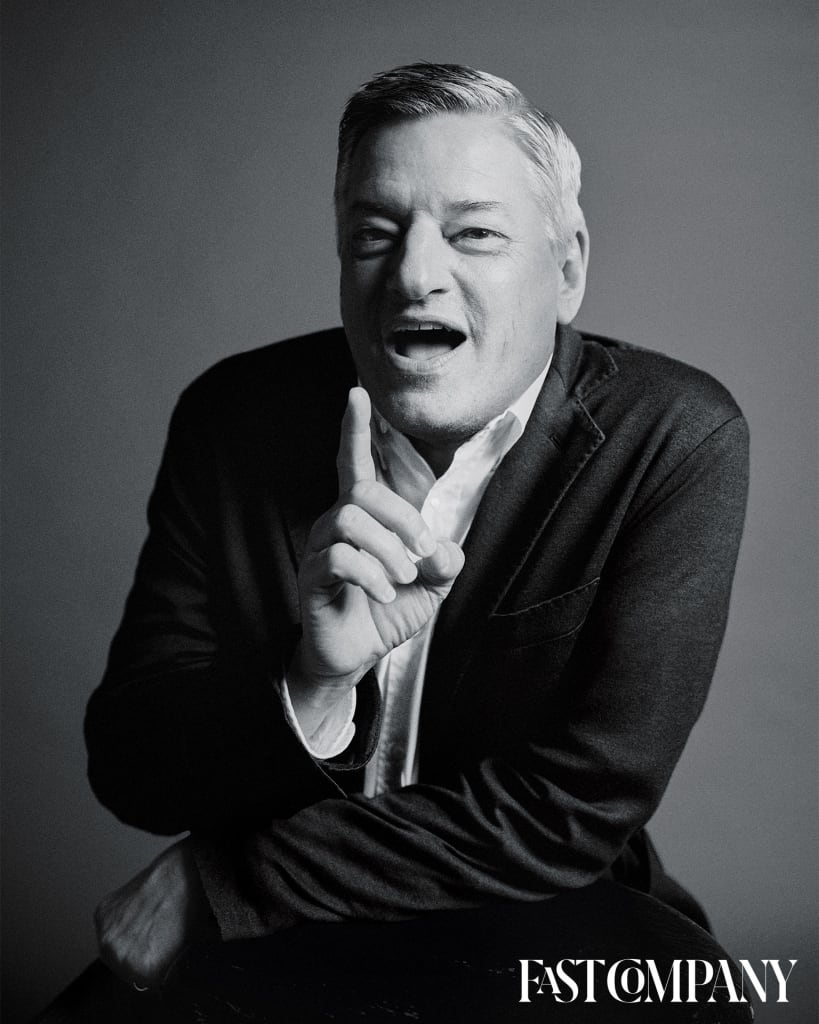

“I was joking yesterday that part of the job of CEO is, like, chief excitement officer,” Sarandos—dressed in his usual jeans, blue blazer, open-necked button-down, and white Italian sneakers—said as we settled into a conference room. (His role includes running point on marketing, legal, communications, and publicity; Greg Peters, who was named Sarandos’s co-CEO when Netflix cofounder Reed Hastings became executive chairman in 2023, takes the lead on product and tech, advertising, human resources, finance, and gaming.) A boyish 60-year-old, Sarandos is a natural schmoozer who easily finds common ground with anyone whose hand he’s shaking. That has been very good for business.

Clik here to view.

Industry wisdom holds that to be profitable, streamers need at least 200 million subscribers. Today, only Netflix, Disney (Disney+ and Hulu combined), and Amazon enjoy that kind of global scale, but Netflix is way out front, with more than half a billion viewers in 190 countries—everywhere but China, Russia, North Korea, and Syria. Sarandos says that on average, subscribers spend two hours a day on the platform, while “most of these other companies are getting two hours a month.” That means Netflix can spread the costs of even very expensive projects over its many users. (The recent series 3 Body Problem reportedly cost $160 million for eight episodes.) “There’s a bigger business in making things 10% better than making them 10% cheaper,” Sarandos said.

“We can produce a $150 million–budget movie and release it only on Netflix and have enough scale to get a return on that investment,” said Sarandos, which at Netflix means high engagement, or number of hours watched—a metric the company now promotes as the best way to value it, not total subscribers. The point is to give members an unending river of content they like so they feel they’ve gotten their money’s worth. That’s how Netflix retains subscribers; it has the lowest churn rate in the business, below 4%. By contrast, Sarandos said, rivals that make pricey content “have to release it on DVD, on pay-per-view, and put it in the theater—any way to possibly monetize it before it gets to their struggling streaming service.”

Everyone at Netflix agrees on one key to its success: data. Even early on, when Netflix was mailing DVDs, the company gathered information on user choices, which in turn fueled algorithms that recommended programming that particular users would likely enjoy. Later, data helped the company pinpoint the moment it should switch from DVDs to streaming. Sarandos, who joined Netflix in 2000 after working in the VHS distribution business, remembers a graph the company kept on the wall then that plotted rising postage costs against bandwidth fees, which were going down. The goal: to identify when streaming technology became affordable enough to attract a groundswell of customers.

“You could look at it and see: If we go too soon, we’re going to license a bunch of content that people can’t watch. And if we go too late, someone’s going to beat us,” Sarandos said. In 2007, the company was among the first to start streaming.

But it was another bold move, in 2011, that would utterly transform Netflix, and the economics of the industry. Though Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes scoffed at the time that Netflix barely posed a threat—“It’s a little bit like, is the Albanian army going to take over the world? I don’t think so,” he said—Netflix soon proved him wrong. Sensing that studios would become more protective about licensing their content, Sarandos felt it was time for Netflix to make its own. When he heard about House of Cards, HBO was in prime position to buy the political thriller, which had director David Fincher attached. But Sarandos won out by green-lighting an unheard-of two seasons, paying $100 million, and promising to deliver “no notes” to the creative team—a rarity.

Today, Sarandos downplays the audacity of that deal, which he made without telling Hastings (and six months after the company had told Wall Street it wouldn’t make originals). But Rich Barton, the cofounder and former CEO of Zillow, who has been on Netflix’s board since 2002, said, “That was a crossing- of-the-Rubicon moment. We moved into a dangerous land: a [potentially] bottomless pit of spending, pitting yourself against your most important suppliers. It’s hard to describe how daring it was.” Hastings told me he considered the move “business-insightful and artistically gutsy. That’s the miracle of Ted.”

When House of Cards premiered in 2013, Netflix released the entire first season at once, inventing the “binge watch.” The show won Netflix its first three Emmys.

Around this time, the company began expanding around the world. (It now has offices in 27 countries.) The company also started making content for global consumers, in their own languages, produced locally. On a few occasions, shows like these would cross over to the rest of the world, as South Korea’s Squid Game did in 2021, attracting more than 2.2 billion viewing hours in its first 91 days. That global reach helped American shows as well. Tyler Perry spent years hearing that “Black movies don’t travel” abroad. Then he began making films for Netflix in 2020 and discovered that “that was and always has been a lie,” Perry said. His movies have hit No. 1 on the platform in 33 countries.

Ted SarandosI think most of this negative reaction to disruption is some belief that you’re entitled to your business model for life. And you’re not. You’re not entitled to your business model, and you’re not entitled to consumer satisfaction. You have to earn it. All the time.”

Like a goldfish set loose in a lake, Netflix grew bigger with every passing day. The reason, Sarandos said: Netflix understands that “you don’t get to make the rules for consumers.” You win “by understanding what they want and giving them what they want. The business model may shift underneath you, but that means you have to shift too.” Today, he said, Netflix’s competitors are struggling because “they’re clinging to these legacy businesses in a way that we never did. I think most of this negative reaction to disruption is some belief that you’re entitled to your business model for life. And you’re not. You’re not entitled to your business model, and you’re not entitled to consumer satisfaction. You have to earn it. All the time.”

This explains Netflix’s embrace of procedurals—and reality shows, and cooking shows, and so many other things that feel . . . familiar. People are complicated, Sarandos said. They like documentaries and telenovelas, star-studded glimpses into the soul of the British monarchy, and comfort food shows, high-brow and low. Netflix supplies it all. “If you’re going to grow engagement, which I think is the number-one metric of the streaming business, you have to have something for everybody,” he said. “Entertain the world.”

It was not long ago that Wall Street sent Netflix a message: Rein it in. When the company said it had lost subscribers in the first half of 2022, its stock plummeted. Netflix responded by laying off employees, cracking down on password sharing, and eventually repositioning itself by creating a lower-priced membership tier supported by ads and adding live programming, including sports. Netflix paid a reported $150 million to air two NFL games on Christmas Day 2024, with an option to do so again in 2025 and 2026. (Meanwhile, Amazon is reportedly paying $1 billion per season for 11 years to be the exclusive home of Thursday Night Football). Hastings told me that the move into live, which also includes roasts (see: Tom Brady) and stand-up comedy specials, is merely “delivery on the brand promise. Love us or hate us, you’ll always be talking about us. We definitely have to be exciting, thrilling, and unpredictable.”

Netflix is clearly hoping that live programming—including all WWE shows, such as Raw, starting next year—will do three things: attract new viewers (in both the ad-supported and ad-free tiers), attract new advertisers (as those new viewers create scale for the ad tier), and make the streamer harder than ever to quit. But speculation that the company might make a distribution deal with a major-league sports franchise is extremely premature, Sarandos said.

As he explained to Dana Carvey and David Spade on their Fly on the Wall podcast earlier this year, there’s so much demand for live sports, and exclusive deals are so expensive, that they become loss leaders; the distributor “doesn’t get much margin for it.” To me, Sarandos repeated that Netflix can grow to even twice its current size merely by continuing its organic global expansion. “About a third of TV watching today is live, and about 20% of that is sports,” Sarandos told me. “But right now, there are so many options for what, how, and where [fans] can watch that in addition to their Netflix subscription.” He said that the company wouldn’t consider making an investment as pricey as a major-league deal until such a deal could be profitable.

Reed Hastings has often attributed Netflix’s success, at least in part, to marriage counseling. As Hastings tells it, years ago a therapist taught him and his wife the importance of radical candor— a tenet that’s still key to the famed (and always evolving) culture memo that lays out how Netflix employees should behave. Today, every Netflix person I talked to said if not for the company’s unusual workplace ethos, which urges employees to “farm dissent,” among other things, its dual-CEO model would not work.

Zillow’s Barton acknowledged that the dual-CEO model (which has been tried, then scrapped, at places such as Salesforce and Oracle) is “not common because it’s not super stable in most situations and with most humans.” But despite their differences, he said, Sarandos and Peters “are completely aligned. They work hard at it.” An executive coach chosen by Hastings still gives feedback to both men, the company confirmed, and so far, the arrangement is working. “I think we get to better decision-making,” said Peters. Sarandos agreed. “Having someone to talk to who is not an employee or a board member—who is your peer—is so helpful,” he said.

Perhaps the biggest test of that partnership has been Netflix’s new ad tier, which costs $6.99 a month (nearly $10 less than its basic ad-free plan). Peters is taking the lead with advertisers, but Sarandos helps out where he can. In November 2022, when the ad tier was announced, Shonda Rhimes made it known that she was unhappy. Just 16 months earlier, the mega-producer (Bridgerton, Grey’s Anatomy) had extended her deal to make content exclusively for the streamer, partially because of its lack of ads. Now, it seemed Netflix had pulled a bait and switch.

Sarandos moved quickly. “I called her, and we talked about it,” he recalled. “She said, ‘No, I’m not against advertising. My whole career is built on advertising. But I just didn’t write Bridgerton for ad breaks.’” Rhimes worried about where the ads would go and how they’d impact the viewing experience. “She raised a good point, which is there’s something really immersive about being in your third hour of a binge,” Sarandos said, laughing as he recalled Rhimes saying she wasn’t sure she wanted “to take viewers out of that for a Lincoln Navigator.”

Sarandos suggested a compromise. “Say we’re going to have four ad breaks,” he told Rhimes, whose company spokesperson confirmed this exchange. “You pick out where they go.” Then they talked about creating “immersive” ad experiences tailored to her fans—featuring Bridgerton cast members, say. Were this or some other brand-related tie-in to occur, Sarandos told me, Rhimes would get paid extra. (Though not all Netflix creators would necessarily enjoy that same participation, he said: “Like all relationship points, it’s bespoke.”)

For his part, Sarandos likes to imagine a day when the streamer will offer multipart narrative ads that unspool in order, even if a member switches from The Gentlemen (an edgy British cannabis caper) to Sweet Magnolias (a so-called laundry-folding show about three best girlfriends living and loving in a town called Serenity). Instead of being embedded in a particular show, these ads would follow the individual members they were chosen for wherever they went.

Netflix isn’t the first streamer with an ad tier. “To give Hulu credit, they really pioneered the choice model on ads,” Hastings said. But because Netflix once positioned itself as the ad-free alternative, its new tier is being closely watched, especially as two high-profile executives, hired to spearhead the effort, have departed. Both CEOs have said ads won’t prompt any programming changes. (Sarandos says ad revenue “will be a relatively small percent of revenue for a long time. So that would really be the tail wagging the dog.”) And they acknowledge that the ad tier needs to grow to attract big advertising dollars. In May, the company reported 40 million global active ad-tier “users” a month (not subscriber households), a number that rose by between 65% and 100%, quarter over quarter, for three quarters before slowing down; in Q1 2024, ad-tier membership grew 34%. But that represents vastly fewer eyeballs than ad-heavy rivals like Amazon Prime (and YouTube) already deliver. In July, Peters told investors the ad tier will get to “critical scale” (whatever that means) by 2025.

Last fall, as two Hollywood strikes ground on, Andrew Garfield—who’d agreed to play the monster in Guillermo del Toro’s live-action Frankenstein—dropped out due to a scheduling conflict. Suddenly, del Toro—who was reteaming with Netflix after winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature for his 2022 Pinocchio—had 72 hours to fill the crucial role.

Sarandos got del Toro on the phone. “Have you seen Saltburn?” he asked. “You should look at Jacob Elordi.” The 27-year-old Australian had starred in Netflix’s The Kissing Booth and HBO’s Euphoria. But it was Saltburn—made by Amazon MGM Studios—that proved Elordi had the range Frankenstein required, Sarandos said.

Guillermo del ToroI said, ‘Listen, either I get this guy in the movie in the next six hours, or I’m not going to make my date.’ And in exactly 45 minutes, the deal was done.”

Sarandos secured a link from MGM so that del Toro could watch Saltburn in Toronto, where he was already in preproduction. Del Toro scheduled a Zoom with Elordi, and “within 30 seconds,” he said, he’d found his new monster. Then agents and lawyers got involved. The clock ticked. Del Toro called Sarandos. “I said, ‘Listen, either I get this guy in the movie in the next six hours, or I’m not going to make my date.’ And in exactly 45 minutes, the deal was done.”

When he told me this story, del Toro was 80 days into Frankenstein’s 108-day shoot. “Over 30 years as a feature filmmaker, I can count on one hand those in charge of studios who have that kind of personal investment,” said del Toro, switching to Spanish to call Sarandos “una persona seria. That means if they say something, it goes. You don’t have to wait for paperwork.”

David Fincher—who, since House of Cards, has made Mindhunter, Love, Sex & Robots, and Mank for Netflix, and has more in development—said Sarandos will call “about some obscure thing that was licensed to Hulu, but it’s going away in three days and ‘You have to see it!’ Marty Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino can regale you for hours about Italian neorealism, but if you want to know what the competitors are up to—and by the way, respectfully!—he’s just in it up to his eyeballs.”

Sarandos consumes a lot of YouTube, for example, which boasts more viewer hours than Netflix (in May, YouTube accounted for 9.7% of all viewership on connected and traditional TVs in the U.S., compared to Netflix’s 7.6%). But in addition to keeping tabs, there’s another reason Sarandos hoovers up rivals’ content, along with everyone else’s: He enjoys it. Sarandos grew up in a chaotic Arizona home in which TV (Norman Lear sitcoms, SNL) provided an emotional center. In his late teens, when he began working at Phoenix’s first video-rental store, he devoured all 900 of its films. Savant-like, he easily summons plots, dialogue, punch lines.

“The fact that he is a cinephile and runs the company that birthed streaming is a paradoxical matter,” del Toro acknowledged. But when it comes to the decline of theater attendance or the slowing of the “Peak TV” boom or even the forces that created last year’s labor unrest (which some dubbed “the Netflix strikes”), he said, it’s simplistic to blame a single streamer.

“Netflix is easy to construct as the villain—you just point to the most visible point on the map,” del Toro said. “But it’s not like the other studios are models of ethics and behavior. They are corporations mostly owned by other corporations.” At least at Netflix, he said, there is a leader with discerning taste and the willingness to assert it when needed. Sarandos, whose compensation last year totaled $49.8 million, told me he loves seeing movies in a theater, which he does “once a month or once a quarter.” He added: “Every time I argue with one of the [movie] studio heads about theaters, I say, ‘It’s funny: I never see you at the theater. I know you have a nice screening room at your house. But the thing you’re trying to protect—how often do you get out and go to one?”

In February, Sarandos flew to South Korea and met with President Yoon Suk Yeol at his home (Netflix plans to spend $6 billion producing content there). He’s had similar meetings with the prime ministers of Canada and Greece, and he will soon receive the Commander of the Order of the British Empire. China is off the table for Netflix, at least for now. “We stopped trying years ago,” Sarandos said, recalling an early licensing deal that fizzled when SARFT, the country’s regulatory board, refused to clear a single Netflix show. But India (population 1.4 billion) is one of Netflix’s fastest-growing markets.

Closer to home, Netflix has solidified plans to buy almost 300 acres in New Jersey, where it intends to build a production facility like Albuquerque’s, but bigger. There, like in New Mexico, the streamer promises to put thousands to work. Won’t AI reduce the need for such brick-and-mortar studios? Sarandos thinks not. “Why am I not worried about AI? Because I’m focused on ambitious and surprising things,” he said. “AI is almost the antithesis of that as a creation tool.”

“Ambitious” and “surprising” are not the words most people would apply to a procedural like Pulse or to older shows such as NCIS, The Office, or Suits, which began on network or cable TV but found new life on the streamer—a phenomenon known as the Netflix Effect. But Netflix seems to have a sixth sense about what viewers want, regardless of when they get to it.

Back in Albuquerque, at the studio’s ribbon-cutting, one Netflix Effect beneficiary stood nearby: Vince Gilligan, the creator of Breaking Bad, who was being honored with a new street sign on the lot. Gilligan told me he will always be grateful to AMC and Sony Television for bankrolling his serialized crime drama, but the show only found a huge audience after Netflix licensed so-called catch-up TV rights. When it streamed the first three seasons just before AMC premiered the fourth, the resulting binge-a-thon helped secure one last season. Then, as now, when Netflix is involved, it seems everything old can be new again.