For fashion brands, making a pair of jeans is a little like gambling.

They must decide what silhouettes will be hot next year: perhaps they bet on horseshoe jeans. Then they order bolts of fabric from mills, which they will send to overseas factories to manufacture. By the time the finished jeans arrive back in the United States, there’s a decent chance nobody will be wearing horseshoe jeans anymore. So the brand will have discount their inventory, or worse, throw them away.

Unspun—founded in 2015 by Stanford alums Beth Esponnette, Walden Lam, and Kevin Martin—wants to transform the system. It has developed technology that allows brands to set up machines in existing factories that will weave yarns into garments within minutes. The founders’ broader vision is to encourage companies to invest in domestic manufacturing, so they can make products closer to their customer. This will allow them to be more agile, deciding what styles to make just weeks, or months, in advance. This, the founders believe, will radically decrease overproduction, slashing global carbon emissions by 1%.

The company has been perfecting its technology for years. But now it’s ready to begin incorporating its machines into the $1.7 trillion global fashion industry. It has just landed $32 million in Series B funding led by tech VC firm DCVC, with participation from Lowercarbon Capital, E12, Decathlon and SOSV.

Unspun has previously worked with smaller brands like Pangaia, Collina Strada, and Eckhaus Latta, which made small capsule collections using Unspun’s machines. It also had its own app that allowed people to custom design jeans. But it is now partnering with larger players like Walmart, and is now primed to keep scaling.

Remaking a supply chain

Over the last century, the global supply chain has become entrenched. In the 1980s, fast fashion brands began growing explosively, relying on overseas factories with low-wage labor and inexpensive fabrics that make trendy clothes. The cost of making each garment is so low, in fact, that brands expect to throw out large quantities of inventory when they don’t hit the right trend.

This is exactly the issue that Unspun is trying to tackle. “There’s been a lot of focus on material innovation,” says Walden Lam, Unspun’s CEO. “Tech companies have come up with more sustainable materials and textile recycling. But the issue of overproduction is fundamentally part of the business model for many fashion brands, and nobody was touching it.”

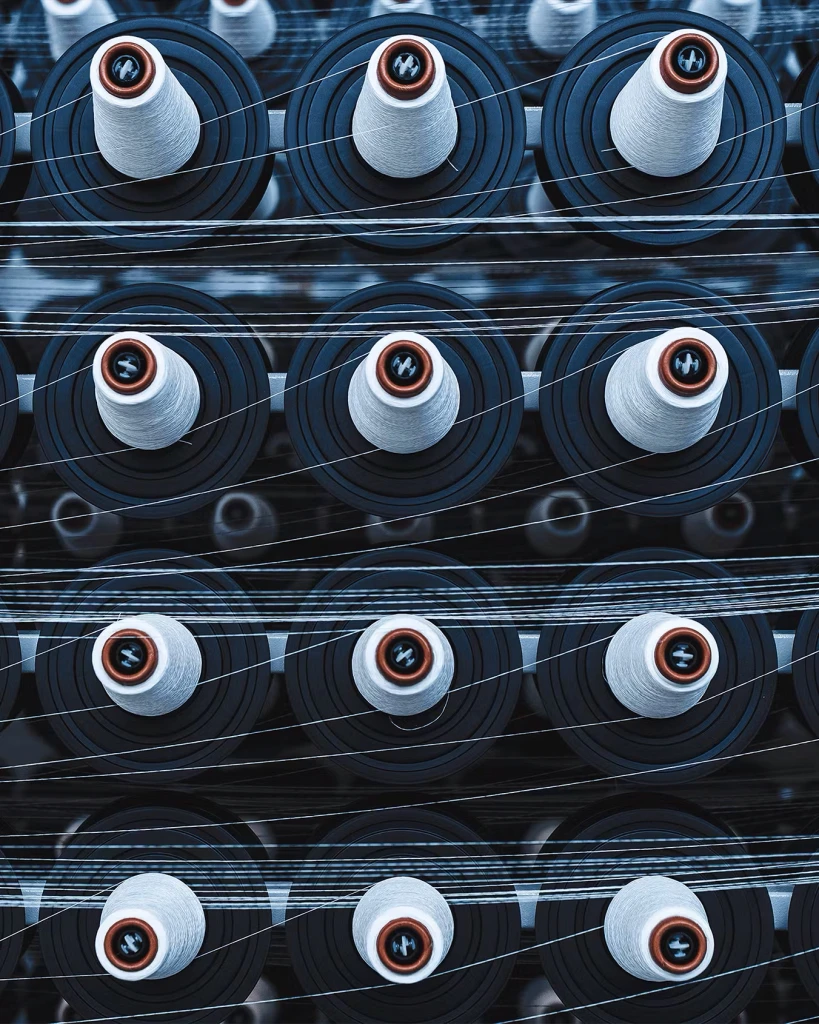

Unspun has now developed a machine called Vega that 3D-weaves yarn quickly and efficiently. It weaves thousands of individual yarns into seamless tubes that make up the core of a garment, like the trouser legs or the body of a T-shirt. The machines operate 10 times faster and five times cheaper than other 3D knitting machines on the market. And it also allows brands to cut out significant amounts of labor required to sew fabrics together.

The company has proven its technology works by partnering with companies, including Walmart, which has piloted Vega machines in several factories that make chinos. It currently makes hundreds of trousers at these factories, but the goal is to make thousands, and then millions by the end of the decade. Unspun’s technology fits into Walmart’s $350 billion investment in making products in America, supporting the creation of 750,000 American jobs.

But going beyond small pilot projects to large-scale change is hard. We saw this with Renewcell, a Swedish startup that built a factory that could recycle fabrics into new fabrics. While there was lots of enthusiasm about Renewcell’s technology and its vision of transforming the fashion industry, it didn’t have enough support from the fashion industry. Companies like H&M and Levi’s had tested Renewcell, but ultimately brands didn’t place enough orders, partly because the Renewcell’s materials are more expensive than others on the market. The company went bankrupt in February. In June, a Swedish investment firm called Altor acquired Renewcell’s assets, and is planning to restart operations.

To survive, technology must solve problems

Rachel Slaybaugh, a partner at DCVC who led this funding round, says that she has faith that Unspun will be able to overcome some of the challenges of scaling. She points out that fashion companies are much more willing to try new technologies if those technologies will ultimately save them money. Unspun, for instance, cuts down on inventory waste, which is an expense that many fashion brands incorporate into their business model.

Unspun also helps brands move toward a domestic supply chain, a transition that many are already exploring. There’s a lot of uncertainty in the global fashion supply chain right now, thanks in part to the Biden Administration imposing new tariffs on Chinese manufacturers to protect American businesses. “Many brands are now forced to consider local manufacturing,” says Slaybaugh. “And Unspun makes their operations more efficient and cost-effective.”

Ultimately, any sustainable solution must solve problems for brands, Slaybaugh says. And it cannot be overly complicated to incorporate into the current supply chain. “Unspun plugs into existing supply chains,” she says. “There’s no need to build a new factory, which is an obstacle many companies can’t overcome.”

Lam also believes regulations will prompt more brands to adopt Unspun’s technology. In Europe, for instance, there are currently new laws in place that forbid brands from destroying or throwing away unsold inventory. Many brands are now thinking about how to reduce overproduction, so they’re not stuck with massive quantities of garments that they don’t know what to do with. “When I worked at fashion brands, it was a headache every season to find charitable organizations to donate your clothes to,” he says. “Many of them don’t want to deal with your overproduction. So given the choice, brands don’t want to deal with the overstock problem. These regulations are catalyzing them to figure out how to cut down on overproduction in the first place.”